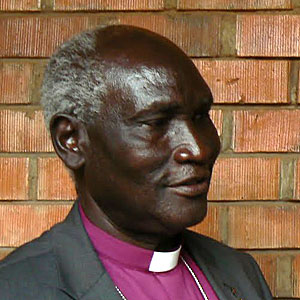

Project Partner, Uganda

Bishop Ochola is the founder of the Acholi Religious Leaders Association and a retired Bishop of the Diocese in Kitgum, Uganda, an area in northern Uganda whose people are suffering from the consequences of war. Bishop Ochola has a deep connection to the war not only because of his ethnic ties but also because he lost his wife and daughter to the war.

Transcript - Excerpt

*Click to download the full transcript.

*Click to listen to the full interview. You will need a DSL connection or better to access the audio file.

Welcome to the Goldin Institute Online's discussion with the Bishop Ochola, the retired Anglican bishop of diocese Kitgum in northern Uganda. The Goldin Institute interviewed Bishop Ochola about his work with the Ochola in Religious Leaders Peace Initiative and about his personal experiences in working with child soldiers. I began our conversation by asking Bishop Ochola to share with us how he became involved in working with child soldiers in Uganda.

Bishop Ochola: Well, mine is a long story. It is started way back when I became a priest in 1972, when [Idi] Amin came into power in '71. I came back from college in the midst of these problems that Amin had created by killing so many soldiers and so many people in Kitgum at the time. I was very much involved in burying the dead and sitting with the grieved families most of the time of my pastoral ministry in northern Uganda. Then from there, you know, I went to, we went into exile in Congo for three years and when we came back, you know the killing in Uganda never stop. So it continued up to today. So my real involvement with the child soldiers actually came about in 1990 when we went back to Gulu. And there were some child soldiers who were in the bush, who are left there, like the current leader of the LRA, Lord's Resistance Army, Joseph Kony, who was part of the child soldiers who were left as nonentity by those who made peace agreement, who signed peace agreement with the Ugandan Government in 1988. So they left them there. So in 1990, when Betty Begombi was appointed the minister for pacification in the north, actually it was she who instated this dialogue with the LRA. So in the course of this, I was involved, I was asked to represent the church. So we used to go many times even during the night to meet with the rebels in the bush. And by 1994, at the beginning of 1994, we succeeded in persuading the LRA to come out of their rebellion. Most unfortunately when the president came to Uganda, to Northern Uganda in Gulu, he gave them a seven day ultimatum that if they don't come out within seven days, they would be flushed out from the bush. But the government never did that up to today. So we started having some soldiers coming back, actually after that one, I mean after the peace process was derailed and the LRA started doing three things. One turn killings through out the villages. Ambushes on all the roads leading out of Gulu or Kitgum, and Lira, and also abductions of innocent children. Those were the three things that the LRA started immediately just after three days of that announcement by the president. So, from 1994 to '99, so many soldiers, so many child soldiers actually, came back, either they were rescued by the government or they escaped and they came into our hands. We began to deal with a big number of children coming out. Sometimes they are officially released by the LRA leaders to come into our hands because we formed what we called the Acule Religious Leaders Peace Initiative in 1997 when the LRA killed over 400 people in Kitgum. Yeah. So that is how I became actually involved in the child soldiers. And we have actually brought so many of them through our organization and sometimes they come through the World Vision International through the- or sometimes they are taken by the army-by the military.

Interviewer: Thank you. Could you tell me, in your experience what are the ages of the child soldiers you have been working with in Uganda and do you know how many are still fighting in the militias?

Bishop Ochola: Well, the child soldiers are anything from seven or six years old to twelve. But now, those who have stayed longer in the bush, depends on how when you are abducted. Because abduction, real abduction actually started over children in 1994 in Kinyeti when the ultimatum was given to the LRA. Soldiers find that young children who have been abducted at the age of 7, and 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, if they stay in the bush for five years, you can add five years to this so you'll know but those who have stayed up to last year or up to now they are more than twenty now. Twenty years old in the bush! Because they have stayed long. But those who have come back, some came back after one year, after three months, after two months or sometimes after five years-you know, they still come out. In 1990--2004, we actually succeeded, in you know, in persuading the government and the LRA to come to meet face to face in the jungle of northern Uganda. We were very grateful because they had wanted to bring thousands and thousands of the children out of the rebellion. But also that was derailed because the government never actually wanted peace.

Interviewer: Do you have a sense of how many children are still fighting or are still looking for a way to escape?

Bishop Ochola: It is very difficult because I didn't go to Garama-I was still in the-in North America. When I arrived there people were already on their way to Gruba and later to Garama so I could not-I cannot give you the precise number. But what I know is that over thirty thousand children have been abducted by the LRA. And they say that half of these have not been accounted for. So you can still say, if it is fifty thousand, that is twenty five are still with them. If it is more than that, then we still have many of them with them. And I belive that there are still very many, there are still very many children with the LRA.

Interviewer: It sounds like several thousand children have found a way to leave the fighting. Is it, in your experience, has it been difficult for them find a way to leave or escape?

Bishop Ochola: Oh, it is extremely difficult to leave because- you see- our work is actually to sensitize the community. We have what we call Peace Committee-all over at the grass roots, in the village sub-county, we have Peace Commitee of nine people. So –what we want actually is to help sensitize our people, so that when those people come they should be received by the community, because our culture is the culture of non-violence, forgiveness, reconciliation and peace. So, this has helped the people to understand us relatively quickly because it is in their blood-they know it, it is their culture. But where, you see people do not understand, like children in school, for instance when child soldiers go to school, they are called - if she's a girl, you know they are still being stigmatized by the children. And even other people who do not understand our culture very well.

Interviewer: I imagine that this sense of reconciliation and forgiveness that you are speaking of, while laudable, must be an extremely difficult proposition for many who have suffered at the hands of child soldiers. There have been many well documented cases of atrocities that these young people have been forced to commit. I understand that this is also an issue that has impacted your family directly and I'm hoping you would share a little bit of your experience and how that impacted your understanding of forgiveness and reconciliation.

Bishop Ochola: I think there are two things here you are talking about. One is that the understanding of the circumstances that lead these children to be where they are in captivity. People should not really judge these children as criminal- as in a sense that they deliberately committed crimes against humanity. They have been forced. It is just like in western world here, if some body kidnaps your child and forces that child to do something. You don't blame the child; you have to blame the kidnapper. So those people who have abducted children and forced them into sex slaves, into child soldiers or made them into instrument of death against their own people-those are the ones to be held responsible. So, for us, as religious leaders and Acule community, our understanding is completely different; that first and foremost that these children are the victims of circumstances. If they have killed us so much, we know that because of the part behind them that forced them to do that. That is our understanding. Which is different completely from other people understanding.

The second point that you have raised, of course, is that one of the victims of this war, my daughter was raped by the by the rebels in 1987, when we were here in North America. And she was gang-raped and after that terrible ordeal, she committed suicide immediately.

Interviewer: I am so sorry.

Bishop Ochola: In May, just four days before her nineteenth birth-date. SO that was a terrible thing for us as a family. Ten years later, my wife went home and when she was coming back on Friday, like today in the morning, her vehicle, the vehicle she was traveling in hit the land mine and she was blown into pieces. She died instantly. That has been actually something that has been very, very difficult in my life and the life of my family.

Interviewer: I'm very sorry.

Bishop Ochola: Never the less, tragic death actually has become a challenge, a very big challenge to me and that is why I have dedicated my whole life to work for peace so that other people may not lose their dear ones unnecessarily as we did. Yes.

Interviewer: Bishop Ochola, thank you again for sharing that story with me and with our listeners. Although that's obviously, a very painful story for me to hear personally, I very much appreciate your willingness to share that with us. As we've spoken about before, I think about you and your story all the time. Your story is one of the reasons why we want to make sure that this issue of child soldiers and the reintegration of child soldiers and the prevention of young people from joining militias is a topic we very much an issue we want to lift up. We know it is an issue around the world. And we look forward to working with you in addressing this issue with our partners and colleagues around the world. Could you share with us where your inspiration or your motivation comes from in tackling these issues despite the many adversities you faced?

Bishop Ochola: Yes. There are two things. One is that I am coming from a culture of non-violence, forgiveness, reconciliation, and peace. And so that is my background where I am coming from. And because of that it has been easier for me to understand when I became a priest, that the same -the same concept, the same understanding of forgiveness and justice is very clear in the Christian principle of reconciliation. The principle of reconciliation is that actually you have to become forgiving. So actually in our culture, this has been a great gift to our people because, in this, what we call mari-put, which is reconciliation in English, it simply means that truth telling is extremely important for accountability. And then, truth telling that means you are revealing what you have down and it is coming out of your own convictions, you are not forced to tell the world. So, actually witness against yourself but witness against what you have done. So that is very important for us. So, I find that in Christianity it is the same principle. It is biblical. It is Christian. So, it helps me to understand God very well when God forgives those who are crucifying Christ on the cross that Jesus Christ prays the prayer of peace-Father, forgive them for they do not know not what they're doing. And you know I have been helped to forgive those who have done all this to me, to my daughter, to my wife, and to my many parishioners who have been killed, even whose graves are not known to anybody. So it has helped me because our culture, or it's system of justice, is very restorative, it is healing, it is forgiving, and it is transforming. That means that if you go through it, you emerge out there a new person, completely transformed, a new community, completely transformed because you have been forgiven, because you have been healed, and because your broken relationship has been restored and because you have now become completely transformed. Yeah. So that helps me to become what I am today. Really, to forgive and to work for peace and to promote the culture of nonviolence for all humanity.